도입부

강화길(1986~)은 한국의 소설가이다. 2012년 데뷔 이후 꾸준히 여성의 이야기를 쓰고 있는 한국문학의 ‘영 페미니스트’ 중 한 사람이다. 19세기 서양 여성 작가들의 고딕 로맨스, 스릴러 장르에 영향을 받았다. ‘믿을 수 없는 화자’를 내세워 독자의 불안을 자극하는 방식을 자주 활용한다. 문학동네 젊은 작가상(2017)과 한겨레문학상(2017)을 수상했다.

생애

1986년 전라북도 전주시에서 태어났다. 어릴 때부터 혼자서 할 수 있는 놀이를 좋아했는데, 독서는 그중에서도 가장 즐거운 놀이었다.1) 10대에는 작가를 꿈꾸었고, 글짓기 대회에서 수상한 경력도 있다. 글을 쓰고 싶어 한국문학과 대학에 진학했으나, 창작 실기 수업이 거의 없어 소설 합평 동아리 활동으로 대신하였다. 진로 고민을 하면서 한 학기를 휴학하고 글쓰기에만 집중하는 시간을 가지기도 했다.2) 작가의 꿈을 이루기 위해 대학원에서 서사창작과를 전공하며 습작을 했다. 2012년 단편소설 〈방〉(2012)으로 데뷔하였다.3)

영 페미니스트4)

등단 이후 줄곧 여성 문제와 관련된 작품을 발표해왔다. 덕분에 작가는 ‘여성주의 작가’, ‘영페미니스트’ 등의 수식어로 소개되고 있다.5) 《괜찮은 사람》(2016), 《다른 사람》(2017) 등은 동시대 여성들이라면 한 번 쯤 겪었을 법한 일상의 불안이 다양한 상황으로 재현되어 있다.

작가는 여성 문제를 중요한 주제라고 생각하고 책임감도 느끼지만, 그것이 자신의 소설의 유일한 목적이 되지 않도록 주의하고 있다. 등단 이후 여성작가가 ‘여성에 대한 이야기’를 쓸 경우 그 프레임에 갇혀 작가의 이미지가 고정될 수 있다는 조언을 많이 받았다고 한다.6) 하지만 강화길은 도리어 그런 규정이 사회적 구조 안에서 발생하는 여성 문제를 개인적인 사건으로 치부하는 프레임에 가두는 것일 수 있다고 생각한다.7) 여성성은 흥미롭고 중요한 주제이며 훨씬 확장될 수 있는 것이기에, 앞으로도 깊이 고민해볼 것이라 한다.8) 따라서 자신은 지금도 여전히 페미니스트가 되어 가는 중이며, 작품을 통해 자신의 세계를 증명해 갈 것이라 말한다.

작품세계

브론테 자매, 메리 셸리 등 19세기 서양 여성 작가들의 작품에 영향을 받았으며, 특히 고딕 로맨스 스릴러 장르의 화법에 깊은 관심을 갖고 있다. 때문에 강화길의 소설은 전반적으로 미스터리 스릴러의 장르 문법과 분위기를 적절하게 이용한다.9) 분위기를 증폭시키는 것은 신뢰할 수 없는 서술자이다.10) 화자의 목소리를 믿고 따라가던 독자가 서술의 어긋남을 직감하는 순간, 화자는 믿을 수 없는 사람으로 뒤집힌다. “뭔가 더 있는 것 같은데 그걸 놓치고 있다는 직감”은 독자의 불안을 자극11)하고, 사건의 이면이 없는지를 생각하게 한다. 하지만 작품에서 불안을 조성하는 모호함은 많은 경우 해소되지 않은 채 끝난다.12)

강화길의 소설 전반을 감싸고 있는 불안과 공포는 여성들의 일상 속에서 마주칠 수 있는 구체적인 사건들과 연결되어 있다. 강화길 소설의 화자는 대부분 여성인데, 자신이 겪은 사건과 자신이 느낀 감정을 말하는 화자의 진술은 어딘가 부족하거나 과민반응처럼 보인기도 한다. 하지만 이런 상황이 반복될수록 독자들은 점차 중요한 것은 여성 화자가 전달하는 사실의 진위 여부가 아님을 알게 된다. 남성들의 본래 의도가 어떠했든 그것을 알 수 없는 여성들은 언제 어디서든 불안을 느낄 수밖에 없다는 것, 그리고 알 수 없는 진실 그 자체가 인간을 병들게 한다는 사실이다.13)

《괜찮은 사람》

《괜찮은 사람》(2016)에는 모두 마음에 병든 사람들이 등장한다. 따라서 왜 하필 그런 인물이고 무엇을 말하려 하는지를 물어야 하는 소설집이다.14) 이는 ‘사람’ 연작15)을 특히 주목해야할 이유기도 하다.

표제작 〈괜찮은 사람〉의 ‘나’는 결혼하려는 남자가 있다. 며칠 전 ‘나’를 다치게 했던 그의 행동이 실수인지 의도인지를 잘 모르고 있는 상태이다. 그의 행동이 배려인지 위협인지 알 수 없는 상황에서 남는 것은 그가 정말 괜찮은 사람인가란 불안이다.

〈니꼴라 유치원-귀한 사람〉에서 아들을 좋은 유치원에 보내려는 ‘나’의 행동이 비틀린 열등감에서 비롯된 것임이 드러난다. 거기다 후보 2번인 민우에게 기회가 온 이유, 유치원을 둘러싼 소문 등이 겹치면서 분위기는 점점 이상해진다. 종국에는 ‘귀한 사람’이란 도대체 무엇인지, 귀한 사람이길 바라는 것이 아들인지 아니면 ‘나’ 스스로인지를 되묻게 만든다.16)

〈호수-다른 사람〉에서는 구체적인 폭행사건이 등장한다. ‘나’와 친구의 연인 이한은 가사상태에 빠진 친구 대신 사건의 진상을 조사한다. 하지만 시간이 갈수록 ‘나’는 이한에게 공포감을 느끼게 된다. 그러나 ‘나’ 또한 이한에게는 사건과 상관없는 의혹만을 던지는 과민한 사람으로 보일 뿐이다. 결국 객관적으로 파악할 수 있는 사실은 친구가 의식불명 상태로 입원했다는 사실 뿐이다. ‘나’와 이한은 사건을 겪지 않은 ‘다른 사람’인 것이다.

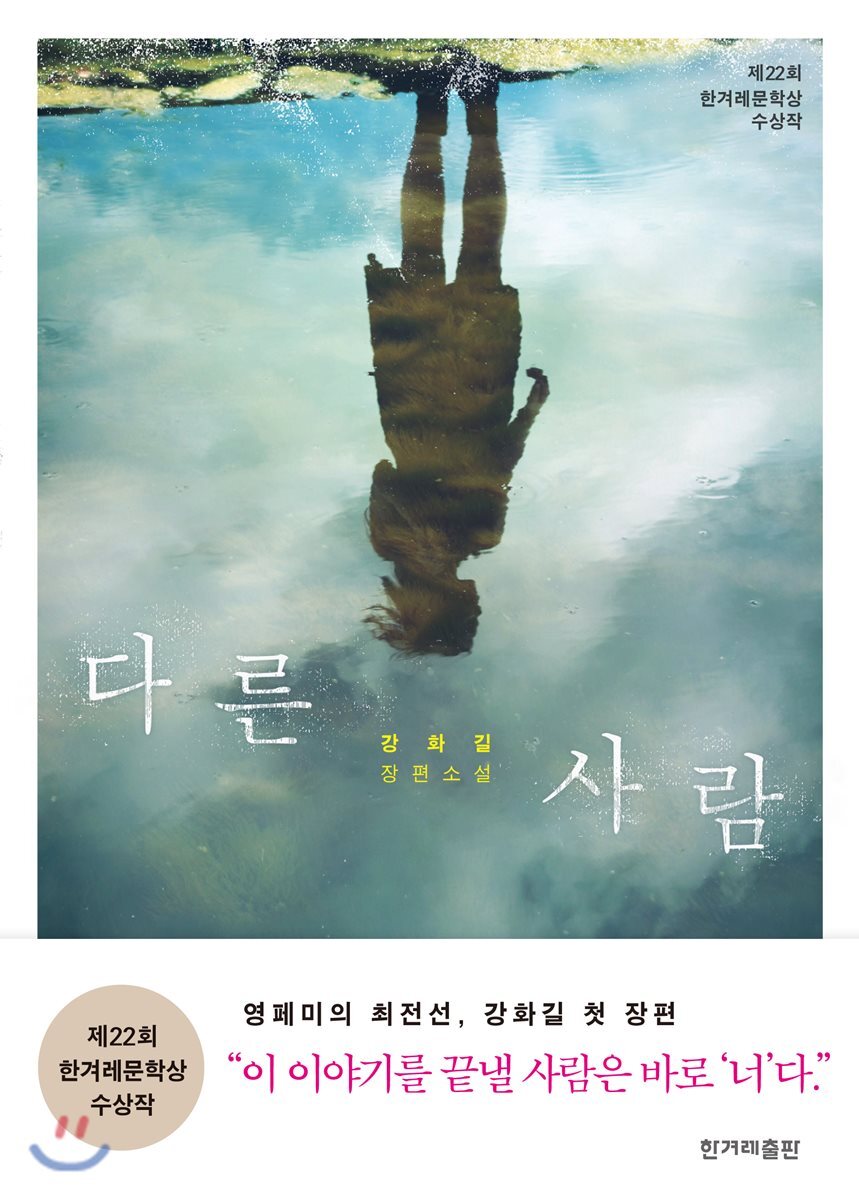

《다른 사람》

장편소설 《다른 사람》(2017)은 데이트 폭력을 당한 진아가 남자친구를 신고하면서 시작한다. 별 볼일 없는 처벌에 화가 난 진아는 인터넷에 사건 경위를 올리지만, 도리어 자신에게 악의적 댓글이 달린다. 그때 자신을 아는 사람이 단 듯한 댓글을 보고, 죽은 친구 유리의 기억을 떠올린다. 서사의 진행에서 두드러지는 것은 데이트 폭력, 온라인 댓글 테러, 학교 내 성폭력 등의 사건이다. 이것들은 개인의 사적 체험 같아 보이지만, 많은 사람들이 감정적으로 공유 가능한 사건임이 밝혀지면서 한국 사회에 만연한 폭력임이 드러난다. 또한 자기혐오, 피해의식, 자기방어를 오가며 자신에게 일어난 일을 이해하려는 진아의 몸부림은 그녀가 과연 우리와 전혀 ‘다른 사람’인가를 묻게 한다. 마지막에 작가의 ‘너’라는 호명은 주변에 만연한 관계 내의 폭력을 보면서도 ‘나는 그 사람들과 다르다’며 외면했던 사람들을 겨냥한다.17)

《서우》

《서우》(2018)는 여성혐오 시대에 있을 법한 도시괴담, 심야택시 탑승의 공포를 이야기한다.18) ‘나’는 여성승객과 여성 운전사 실종 사건이 일어나고 있는 동네를 가기 위해 택시를 탄다. ‘나’는 여성운전사이기에 마음을 놓고 탑승했지만, 이내 남성운전사들과 닮은 그녀의 불쾌한 언행은 ‘나’의 신경을 건드린다. 하지만 반전은 ‘여성도 가해자일 수 있다’에서 끝나지 않는다. 사이코패스 같은 ‘나’의 과거 기억이 드러나면서 그녀는 ‘신뢰할 수 없는 화자’이자 사건의 유력한 용의자로 변한다. 《서우》는 도시괴담의 전형적인 구조를 비틀고, 아무것도 모르는 피해자란 여성의 위치도 비튼다.

주요작품

1) 소설집

《괜찮은 사람》, 문학동네, 2016.

《우리는 사랑했다》, 키미앤일이, 미메시스, 2018.19)

2) 장편소설

《다른 사람》, 한겨레출판, 2017.

3) 테마소설

〈황녀〉, 강화길 외, 《우리는 날마다》, 걷는 사람, 2018.

〈카밀라〉, 《사랑을 멈추지 말아요》, 큐큐, 2018.

〈꿈엔들 잊힐 리야〉, 《멜랑콜리 해피엔딩》, 작가정신, 2019.

번역된 작품

《서우》 k-픽션 22, 도서출판 아시아, 2018.20)

수상 내역

2017년 한겨레문학상 (수상작 《다른 사람》)21)

2018년 구상문학상 젊은 작가상(수상작 2018년 《서우》)22)

참고 문헌 (References)

1) 〈강화길 “독서는 지극히 개인적인 경험”〉, 《채널예스》, 2017.09.27.

http://ch.yes24.com/Article/View/34395

2) 윤효정, 〈소설가 강화길 "여성 문제? 당연히 쓸 수밖에 없는 문제라 썼다"〉, 《book db》, 2017.10.10.

http://news.bookdb.co.kr/bdb/Interview.do?_method=InterviewDetail&sc.mreviewTp=1207&sc.mreviewNo=81043&Nnews

한윤정, 〈“현재 문학은 허용된 범위 안에서만 정치적 자유 누릴 뿐”〉, 《경향신문》, 2012.01.15.

http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?artid=201201152142185&code=960100

3) 데뷔 관련 에피소드가 하나 있다. 주최 측에서 작가의 신상정보를 잃어버리는 바람에 연락처를 찾기 위해 인터넷 검색을 해야만 했다. 학교 수업을 위한 인터넷 카페에서 ‘국문과 강화길’의 정보를 겨우 찾아 부모님 집으로 연락을 할 수 있었다. 작가는 부모님으로부터 당선 연락을 받았고, 본인이 직접 주최측으로 전화를 했다고 한다.

한정구, 〈강화길 “말하지 못할 뿐, 너무 흔한 일이에요”〉, 《채널예스》, 2017.09.13.

http://ch.yes24.com/Article/View/34296

4) 영페미(Young Feminist) 작가는 이전 세대의 여성작가들(1990~2000년대)과는 차별화된 시각을 지닌 젊은 여성작가, 즉 세대적 구분이 담겨있다. 또한 이전 세대가 여성이 겪는 폭력의 문제를 은유적으로 표현했다면, 이들은 여성을 직접 정치적 주체로 그려낸다. 여성을 향한 갖가지 폭력과 싸우려하는 사회적 요청에도 문학을 통해 적극적으로 응한다는 점에서 달라진 방식을 확인할 수 있다. 구체적으로 최은영, 조남주, 강화길, 박민정 등이 있다.

이윤주, 〈‘페미니즘 열풍’ 의미있는 흐름 만들어〉, 《한국일보》, 2017.12.28.

https://www.hankookilbo.com/News/Read/201712281794644576

정서린, 〈[2017 문화계 결산] 성찰 부른 女風… 위로 건넨 대화〉, 《서울신문》, 2017.12.21.

http://www.seoul.co.kr/news/newsView.php?id=20171222024011&wlog_tag3=naver

5) 윤효정, 〈소설가 강화길 "여성 문제? 당연히 쓸 수밖에 없는 문제라 썼다"〉, 《book db》, 2017.10.10.

http://news.bookdb.co.kr/bdb/Interview.do?_method=InterviewDetail&sc.mreviewTp=1207&sc.mreviewNo=81043&Nnews

이윤주, 〈‘페미니즘 열풍’ 의미있는 흐름 만들어〉, 《한국일보》, 2017.12.28.

https://www.hankookilbo.com/News/Read/201712281794644576

6) 임나리, 〈강화길 “말하지 못할 뿐, 너무 흔한 일이예요”〉, 《채널예스》, 2017.09.13.

http://ch.yes24.com/Article/View/34296

7) 영상 인터뷰, 〈[#책 3회] 다른 사람(강화길)〉, 《한겨레》, 2017.09.28.

http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/culture/book/812907.html

8) 임나리, 〈강화길 “말하지 못할 뿐, 너무 흔한 일이예요”〉, 《채널예스》, 2017.09.13.

http://ch.yes24.com/Article/View/34296

9) 작가는 19세기 여성 작가들의 고딕 로맨스 스릴러에 꾸준히 관심이 있다고 밝혔다. 제한된 공간과 미스터리, 스릴러에 더하여 안전하다고 생각한 로맨스가 사실은 아무것도 아닌 이야기로 밝혀지는 이야기들. 이를 반영하듯 《괜찮은 사람》의 지은이의 말은 셜리 잭슨의 문장이 인용되어 있다.(“I am the captain of my fate. Laughter is possible laughter is possible laughter is possible.”- Shirley Jackson) 평자는 이 문구가 남편에게 정서적 학대를 당했던 시기에 쓰였음을 밝히며, ‘여성해방’이라는 주제를 환기시킨다고 평한 바 있다.

〈강화길 “독서는 지극히 개인적인 경험”〉, 《채널예스》, 2017.09.27.

http://ch.yes24.com/Article/View/34395

《괜찮은 사람》 책소개

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=97804554

10) 노대원, 〈비평의 목소리〉, 《서우》, 도서출판 아시아, 2018.

12) 《괜찮은 사람》 책소개

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=97804554

13) 황현경, 〈모르는 사람〉, 《괜찮은 사람》, 문학동네, 2016.

14) 《괜찮은 사람》 책소개

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=97804554

15) 황현경, 〈모르는 사람〉, 《괜찮은 사람》, 문학동네, 2016.

16) 작가는 한 인터뷰에서 ‘사람’시리즈 단편을 쓰기 시작했고, 이는 장편인 《다른 사람》(2017)으로 확장되었음을 밝힌 바 있다.

영상 인터뷰, 〈[#책 3회] 다른 사람(강화길)〉, 《한겨레》, 2017.09.28.

http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/culture/book/812907.html

16) 《괜찮은 사람》 책소개

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=97804554

17) 《다른 사람》 책소개

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=116056770

18) 오혜진, 〈‘즐거운 살인’과 ‘여성스릴러’의 정치적 가능성〉, 《서우》, 도서출판 아시아, 2018.

19) 이 책은 ‘테이크아웃’ 시리즈로, 젊은 소설가 20명과 일러스트레이터 20명을 매치하여 이야기와 이미지를 함께 즐길 수 있도록 기획된 책이다. 강화길은 5번째로 참여했으며, 일러스트레이터 키미앤일이와 작업하였다.

《우리는 사랑했다》 책소개

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=152565925

미메시스 출판사 블로그, 테이크아웃 시리즈 소개

https://m.post.naver.com/viewer/postView.nhn?volumeNo=15948777&memberNo=4806582&navigationType=push

20) 《서우》 책소개

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=158946993

21) 최재봉, 〈“‘다른 사람’의 일이 아니라는 것 말하고 싶었어요”〉, 《한겨레》, 2017.05.25.

http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/culture/book/796208.html

22) 〈구상문학상에 김해자, 젊은 작가상엔 강화길〉, 《연합뉴스》, 2018.11.08.

https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20181108043600005

데뷔작 〈방〉 TEXT 링크-〈[2012 경향 신춘문예]소설 부문/ 강화길-방〉, 《경향신문》, 2012.01.01.

http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?artid=201201012012425

Introduction

Kang Hwa Gil (born 1986) is a South Korean writer. She is one of the “young feminists,” who has consistently written about women since her literary debut in 2012. Her writing has been influenced by gothic romance and thrillers written by women writers in the 19th century. She often employs the use of “unreliable narrators” to trigger the reader’s anxiety. She is a recipient of the Munhakdongne Young Writers’ Award (2017) and the Hankyoreh Literary Award (2017).

Life

Kang was born in Jeonju, North Jeolla Province, in 1986. Since her childhood, she enjoyed activities that could be performed alone, and reading was her favorite activity by far.[1] In her teens, she dreamed of becoming a writer and received prizes in writing contests. She became a Korean literature major to write, but the lack of creative writing classes led her to join a joint literary review club in college. While considering her future career, she took a semester off from college and focused on writing.[2] To achieve her dream of becoming a writer, she enrolled in a graduate program for narrative creation and continued to write. In 2012, she made her literary debut with the short story “Bang” (방 Room).[3]

Young Feminist[4]

Since her debut, Kang has consistently written about issues related to women, which earned her the description “feminist writer” and “young feminist.”[5] Stories in Gwaenchaneun saram (괜찮은 사람 A Good Person) (2016), Dareun saram (다른 사람 A Different Person) (2017) are laced with anxieties contemporary women have felt at one point in time or another in various situations.

Kang believes that women’s issues are an important topic and also feels a sense of duty to write about them, but she takes care not to make them the sole aim of her work. She said that many people warned her about the possibility of being stereotyped as a woman writer who writes about women, since her debut.[6] However, Kang believes that such self-regulation can end up limiting women’s issues that occur within the social structure to personal problems.[7] She is planning to continue and delve into femininity, as it is an interesting and important topic that can be further expanded.[8] She says that she is still in the process of becoming a feminist, and she will strive to show her world through her works.

Writing

Kang was influenced by the works of 19th-century Western women writers, including the Brontë sisters and Mary Shelley, and is particularly interested in the gothic romance and thriller narratives. So Kang’s fiction makes use of the grammar and atmosphere of mystery thrillers in general.[9] In addition, unreliable narrators in Kang’s stories heighten the sense of mystery.[10] When the reader, who has been following and trusting the voice of the narrator, realizes the ruptures in the narrative, the narrator becomes an unreliable person. The hunch that there is something else that you cannot quite put your finger on intensifies the reader’s anxiety[11], leaving the reader to wonder what is underneath the surface of the story. Often the ambivalence that feeds the reader’s anxiety is left unresolved in the work.[12]

The anxiety and fear that envelopes Kang Hwa Gil’s stories are linked to the specific real-life events that women in our society encounter in their daily lives. Most of the narrators in Kang’s stories are women, and their statements about their feelings and experiences tend to seem somewhat lacking and at times make them seem overly sensitive. However, as these situations recur, the reader gradually realizes that whether or not what the narrators are saying is true is not the issue at hand. The point is that women cannot but feel anxious and fearful when left in the dark about men’s intentions even if they are good intentions—and the unknowable truth brings suffering upon humans.[13]

Gwaenchanneun saram

Gwaenchanneun saram (2016) is a short story collection that features stories with characters who are troubled at heart. It makes the readers ask why the author wrote such characters and what she wants to say through them.[14] This is a reason why we also need to look closely at Kang’s saram (person or people) series.[15]

In the titular story “Gwaenchanneun saram,” the first-person narrator has a fiancé. But she is unsure whether the action of her fiancé, which resulted in her getting hurt, was accidental or intentional. Without knowing whether his action was a result of his consideration for her or a threat, the narrator is left to anxiously wonder whether he really is a good person or not.

“Nikkola yuchiwon-gwihan saram” (니꼴라 유치원-귀한 사람 Nikola Kindergarten – A Precious Person 니꼴라 유치원-귀한 사람) features a narrator who wants to send her son to a respectable kindergarten, out of a twisted feeling of inferiority. The mysterious atmosphere of the story continues to build, as the narrator learns the reason her son who was second on the waiting list received the chance to attend the kindergarten and hears strange rumors about the kindergarten. Toward the end of the story, it makes the reader question what a “precious person” is and whether the narrator wishes her son or herself to be a “precious person.”[16]

“Hosu-dareun saram” (호수-다른 사람 Lake-Other People) begins with an assault. When her friend is found assaulted, the first-person narrator begins to look into what happened to her friend along with the friend’s boyfriend named Ihan. However, as time passes, the narrator feels terrorized by Ihan, but to Ihan she appears to be an overly sensitive person who asks questions that are unrelated to the incident. The only objective fact is that her friend is lying unconscious in the hospital. The narrator and Ihan are “other people” who were not the victims of assault.

Dareun saram

Kang Hwa Gil’s novel Dareun saram (2017) begins with Jin-a, who was subjected to dating abuse, calling the police on her boyfriend. Upset about the soft punishment the perpetrator received, Jin-a writes about what happened to her online but ends up getting hurt by vicious comments about her instead. While scrolling through the comments, she notices one that seems to have been written by someone who knew her in the past and is reminded of a friend named Yu-ri, who died. The narrative continues with stories of dating abuse, hate comments on the internet, and sexual assault in school. Although initially these experiences seem personal, they are eventually revealed to be violence pervasive in Korean society, shared by many people. In addition, Jin-a’s struggle to understand what happened to her as she experiences self-hatred, victim mentality, and self-defense makes the reader wonder if she really is a “different person” from us. At the end of the novel, the author writes “you,” pointing to the people who neglected the victims of abuse around them, thinking that they were different.[17]

Seo-u

Seo-u (서우) (2018) is a story that combines the fear of taking a cab late at night and an urban legend that has become plausible in the era of misogyny.[18] The first-person narrator takes a cab to go to a neighborhood where female cab drivers go missing. The narrator gets into the cab feeling safe as the driver is a woman, but her unpleasant speech is reminiscent of male cab drivers and the narrator soon grows uncomfortable. However, the twist does not end with the point that women can also be perpetrators. As the story about the narrator’s psychopathic tendencies in her childhood surfaces, suddenly the narrator turns into an unreliable narrator and a key suspect. Seo-u distorts the typical structure of an urban legend and also puts a twist into the idea that women are clueless victims.

Works

1) Short Story Collections

《괜찮은 사람》, 문학동네, 2016 / Gwaenchanneun saram (A Good Person), Munhakdongne, 2016

《우리는 사랑했다》, 키미앤일이 그림 미메시스, 2018 / Urineun saranghaetta (We Loved), illustrated by Kimi and 12, Mimesis, 2018[19]

2) Novel

《다른 사람》, 한겨레출판, 2017 / Dareun saram (A Different Person), Hani Book, 2017

3) Themed Fiction

〈황녀〉, 강화길 외, 《우리는 날마다》, 걷는 사람, 2018 / “Hwangnyeo” (Imperial Princess), Kang Hwa Gil et al., Urineun nalmada (Everyday We), Walker, 2018

〈카밀라〉, 《사랑을 멈추지 말아요》, 큐큐, 2018 / “Camila,” Sarangeul meomchuji marayo (Don’t Stop Loving), QQ Books, 2018

〈꿈엔들 잊힐 리야〉, 《멜랑콜리 해피엔딩》, 작가정신, 2019 / “Kkumendeul ichilliya” (Could Not Be Forgotten Even In a Dream), Melangcoli haepiending (Melancholic Happy-Ending), Jakkajungsin, 2019

Works in Translation

《서우》 k-픽션 22, 도서출판 아시아, 2018 / Seo-u, K-Fiction 22, ASIA, 2018[20]

Awards

Munhakdongne Young Writers’ Award (2017)

Hankyoreh Literary Award (2017) (for Dareun saram)[21]

Ku Sang Literature Prize for Young Writers (2018) (for Seo-u)[22]

References

[1] “Kang Hwa Gil, ‘Reading is an Extremely Personal Experience,’” Channel Yes, September 27, 2017.

http://ch.yes24.com/Article/View/34395

[2] Yun, Hyo-jeong, “Writer Kang Hwa Gil, ‘Women’s Issues? I Wrote About Them Because They Had to be Written About,” Book DB, October 10, 2017.

http://news.bookdb.co.kr/bdb/Interview.do?_method=InterviewDetail&sc.mreviewTp=1207&sc.mreviewNo=81043&Nnews

Han, Yun-jeong, “Contemporary Literature Only Enjoys Political Freedom Within the Permitted Limit,” Kyunghyang Shinmun, January 15, 2012.

http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?artid=201201152142185&code=960100

[3] There is an anecdote related to Kang’s literary debut. The organizers of the literary competition lost her personal information and had to search online for her contact information. They eventually found information for “Kang Hwa Gil, Korean Literature Department” from an internet message board for a class and contacted her parents. Kang learned about receiving the literary prize from her parents and called the organizers back to confirm.

Im, Na-ri, “Kang Hwa Gil, ‘It Doesn’t Get Talked About, But It Happens All the Time,” Channel Yes, September 13, 2017.

http://ch.yes24.com/Article/View/34296

[4] “Young Feminists” refer to younger women writers who have different perspectives than the women writers of the previous generation (1990s and 2000s). While the women writers of the previous generation metaphorically alluded to violence against women in their writing, Young Feminists directly paint women as political agents. They differ from the previous generation of women writers in that they actively respond through literature to the social request to fight against the various violence against women. Young Feminists include Choi Eunyoung, Cho Nam-ju, Kang Hwa Gil, and Park Min-jung.

Lee, Yun-ju, “The ‘Feminism Fever’ Is Creating a Meaningful Trend,” Hankook Ilbo, December 28, 2017.

https://www.hankookilbo.com/News/Read/201712281794644576

Jeong, Seo-rin, “[2017 Culture] Women’s Wave Brings About Social Introspection, Offering Comfort Through Dialogue,” Seoul Shinmun, December 21, 2017.

http://www.seoul.co.kr/news/newsView.php?id=20171222024011&wlog_tag3=naver

[5] Yun, Hyo-jeong, “Writer Kang Hwa Gil, ‘Women’s Issues? I Wrote About Them Because They Had to be Written About,” Book DB, October 10, 2017.

http://news.bookdb.co.kr/bdb/Interview.do?_method=InterviewDetail&sc.mreviewTp=1207&sc.mreviewNo=81043&Nnews

Lee, Yun-ju, “The ‘Feminism Fever’ Is Creating a Meaningful Trend,” Hankook Ilbo, December 28, 2017.

https://www.hankookilbo.com/News/Read/201712281794644576

[6] Im, Na-ri, “Kang Hwa Gil, ‘It Doesn’t Get Talked About, But It Happens All the Time,” Channel Yes, September 13, 2017.

http://ch.yes24.com/Article/View/34296

[7] Video interview, “#Book Episode 3: Dareun saram (Kang Hwa Gil),” Hankyoreh, September 8, 2017.

http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/culture/book/812907.html

[8] Im, Na-ri, “Kang Hwa Gil, ‘It Doesn’t Get Talked About, But It Happens All the Time,” Channel Yes, September 13, 2017.

http://ch.yes24.com/Article/View/34296

[9] Kang expressed her interest in gothic romance thrillers written by 19th-century women writers—stories characterized by limited space, elements of mystery, and romance that was thought to be safe but is not. As though reflecting her thoughts, Kang quotes Shirley Jackson in the writer’s note for Gwaenchanneun saram: “I am the captain of my fate. Laughter is possible laughter is possible laughter is possible.” The reviewer of Kang’s book clarified that Jackson said this at a time when she was being emotionally abused by her husband and brings our attention to the topic of “women’s liberation.”

“Kang Hwa Gil, ‘Reading is an Extremely Personal Experience,’” Channel Yes, September 27, 2017.http://ch.yes24.com/Article/View/34395

Book information for Gwaenchanneun saram

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=97804554

[10] Roh, Dae-won, “Critical Acclaim,” Seo-u, ASIA, 2018.

[12] Book information for Gwaenchanneun saram

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=97804554

[13] Hwang, Hyeon-gyeong, “Moreuneun saram” (Someone We Don’t Know), Gwaenchaneun saram, Munhakdongne, 2016.

[14] Book information for Gwaenchanneun saram

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=97804554

[15] Hwang, Hyeon-gyeong, “Moreuneun saram” (Someone We Don’t Know), Gwaenchaneun saram, Munhakdongne, 2016.

[16] In an interview, Kang explained that she started writing the “people” series, which eventually led to her novel Dareun saram (2017).

Video interview, “#Book Episode 3: Dareun saram (Kang Hwa Gil),” Hankyoreh, September 8, 2017.

http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/culture/book/812907.html

[16] Book information for Gwaenchanneun saram

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=97804554

[17] Book information for Dareun saram

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=116056770

[18] Oh, Hye-jin, “The Political Possibilities of ‘Pleasurable Murder’ and ‘Women’s Thrillers,’” Seo-u, ASIA, 2018.

[19] This book is part of the “Take-Out” series, in which 20 young writers have been paired up with 20 illustrators to create books with matching illustrations. Kang participated in the fifth installment of the series along with illustrator Kimi and 12.

Book information for Urineun saranghaetta

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=152565925

Mimesis Blog, Introduction of the Take-Out Series

https://m.post.naver.com/viewer/postView.nhn?volumeNo=15948777&memberNo=4806582&navigationType=push

[20] Book information for Seo-u

https://www.aladin.co.kr/shop/wproduct.aspx?ItemId=158946993

[21] Choi, Jae-bong, “’I Wanted to Say That Things Like This Don’t Just Happen to Someone Else,’” Hankyoreh, May 25, 2017.

http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/culture/book/796208.html

[22] “Ku Sang Literature Prize Grand Prize Goes to Kim Hae-ja, Young Writer’s Prize Goes to Kang Hwa Gil,” Yonhap News, November 8, 2018.

https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20181108043600005

Short Story “Bang”: “’2012 Kyunghyang Daily News New Writer’s Award for Fiction / Kang Hwa Gil – ‘Bang,’” Kyunghyang Shinmun, January 1, 2012.

http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?artid=201201012012425