[Turkish] Gazing upon the Trembling Statue: Badem (Almond) by Sohn Won-pyung

by Sema Kaygusuz , on April 13, 2022

- English(English)

- Turkish(Türkçe)

now i’ve found the great wall of china

that everyone sensed encircled madly

now everyone’s irked insensibly

so now i get myself into deep water.

Turgut Uyar

A few years ago, as I wandered the EphesusArchaeological Museum where the ruins of the ancient city of Ephesus are ondisplay, I saw a little boy standing stock-still, his eyes fixed on the eyes ofthe statue of Antinous. Though his mother persistently kept calling him to herside, the boy couldn’t pull himself away from Antinous’s attentive gaze, thestatue’s neck turned to the side. He gazed upon Antinous as though he could,just by looking, fill in the missing parts of that familiar object. At thetime, I’d thought of the boy’s frozen stance in front of the statue as a kindof admiration, but now when I envision the scene, a different possibility comesto mind. The boy, his fresh ego filled to the brim with curiosity and wonder,was waiting for Antinous, who hadn’t budged for approximately 1,900 years, toblink. Waiting for that inveterate statue, filled with emotion, to tremble.

Dwelling on the gaze of that boy as he tried toovercome the sharp border between human and human-statue, dwelling on hisinsistent, staring, expectant focus, I think now about the borders of theobject in his focus, about how the border is itself bounded by everything else,about how every border in our world of perceptions is boundless. And indeed,although we cannot comprehend the bounds of the universe, even the universeitself has a border. Just as we can’t comprehend the boundlessness of so manyemotions whose names we don’t yet know.

Last year, a Korean novel titled Badem (Almond) was releasedin Turkish. A “silent” novel in Turkish for the moment, it hasn’t yet beennoticed by readers. And yet, the novel’s senses are open, even as theprotagonist begins his life utterly lacking in emotion due to the insufficientdevelopment of the amygdala in his brain. This is the border that leaves himoutside of culture. He describes emotions by following the traces they leave inthe body, trying to recognize them by describing each one. Like a written text,he attempts to take on each emotion by rationalizing it. The ego, shaped byanger, trauma, and relationships, is, in his ghostliness, a perpetually blankpage. If what we call the ego is an orb of consciousness endlessly pulsing andbleeding in the tower of childhood, then the protagonist of Almond is shrewd but sans ego. He is a freak of nature.As a consequence, we might name him directly by his illness—Alexithymia, theinability to recognize emotions. The organic, pathological border ofAlexithymia makes the protagonist brave, for he knows no fear; tranquil, for heknows no joy; calm, for he knows no rush. In these times when we are trying tohear our inner selves, when we are learning to grapple with our egos throughdifferent kinds of meditation, Alexithymia appears as a freak of nature, as a realphenomenon in the face of the modern person imprisoned by emotions. Though hisbasic senses are highly developed, he lacks the intuition, instincts, andfaculties to turn whatever he touches into individual images or figures ofspeech, and he remains stuck in the realm of description. Because the reasonthe protagonist has been so successful in the realm of description is his lackof poetry. Or, more figuratively, his lack of a heart. It is remarkable thatthe habitat that Alexithymia narrates over the course of the story, purged asit is of emotion and thus of soul, is girded with such towering description.Life exists but its sensuous trace is missing. While the past becomes absolutein material forms, the mind cannot escape from its chronological ordering in analbum. The past, instrumentalized by Chronos, comes to resemble a vacantlandscape, completely disconnected from Cosmos’s involuted, polysemousperceptions. In this novel about a person who is nothing more than arationalized body, the story’s tragic weight is left entirely to the reader. Wefind ourselves taking on all the emotions in this poignant story.

It’s almost as though the statue might tremble,isn’t it? At any moment it might tremble: it is about to tremble.

We might read Almond as a novel that rather strikingly demonstratesthe possibility of a past without memory. In order to survive and to adapt tosociety, the protagonist has to cast off the appearance of having a heart ofstone by learning the common behaviors that emotions elicit. But that does notsuffice. Because adapting to one’s environment isn’t what makes a human human,but the oikos that forges him into something incomparable. A person in pursuitof the descriptions, figures of speech, and images that abstract the world,from the crudest to the most refined, finds his ego.

This novel maps out an unexpected route forthinking about the connections between borders, passages, and transformations;it reverses the usual path that emotions take from the heart to the brain,starting its adventure instead in the brain and coming to an end in the heart.One of the most striking insights that the novel offers the reader through itswayward references is this: that the well of morality is the heart, while thebrain is simply a living abode where moral law is governed. Another significantinsight is that counterparts never become one another. When it comes to theego, every dissimilarity that approaches another, that collides in approach,that bleeds in collision, serves as a sacred text to the outcast. Just asAntinous has stood for 1,900 years, about to tremble in the eyes of a boy, sothe boy there, too, is a prospective poet, ready to be sculpted by Antinous.

artık buldum herkesin çılgınca sezdiği

kıyısında dolaştığı yüksek çin duvarını

artık herkesin belli belirsiz sezdiği

artık kendim ısıtıyorum sularımı.

Turgut Uyar

Birkaç yılönce Efes Antik Kent kalıntılarının sergilendiği Efes Arkeoloji müzesinidolaşırken, olduğu yerde kıpırdamadan gözlerini heykel Antinous’un gözlerinedikmiş bir oğlan çocuğu görmüştüm. Annesi ısrarla onu yanına çağırmasına karşın,oğlan Antinous’un boynunu yana çevirmiş biçimde attığı ilgili bakıştan kendinialamıyordu. Tanıdık olduğu bir nesneyi bakışlarıyla tamamlıyormuş gibibakıyordu Antinous. O sırada heykelin karşısında oğlanın kalakalışını bir çeşithayranlık diye düşünmüştüm, bugün aynı sahne gözümde canlandığında farklı bir olasılıkgeliyor aklıma. Oğlan, bu tepesine kadar merak ve sanıyla dolmuş taze benlik,yaklaşık 1900 yıldır kıpırdamayan Antinous’un gözünü kırpmasını bekliyordu.Duyguyla dolmuş mazmun bir heykelin kımıldamasını.

İnsan ileinsan-heykeli arasındaki keskin sınırları aşmaya çalışan o oğlanın bakışını, onungöz kırpmaksızın bekleyen ısrarlı odaklanışı anımsarken, odaktaki nesneninsınırlarını, sınırın kendinden başka her şeyle sınırlı olduğunu, hatta algıdünyamızda her sınırın hudutsuz olduğunu düşünüyorum şimdi. Öyle ya evren bilesınırlıdır, ama evrenin hududunu kestiremiyoruz. Henüz adını bile bilmediğimiznice duygunun hudutsuzluğunu kestiremediğimiz gibi.

Geçtiğimizyıl Türkçede Koreli yazar Won-pyung Shon imzalı Badem adlı bir romanyayımlandı (çevirmen Levent Dövücü, yayıncı Peta Kitap). Şu an için Türkçede sessizbir roman Badem, henüz okuru tarafından fark edilmedi. Gelgelelim romanınbütün duyuları açık, öte yandan duygudan tümüyle yoksun kahramanı beynin içindeyer alan amigdala yeterince gelişmediği için kelimenin tam anlamıyla hayataduygusuz başlar. Onun kültür dışı kılan bir sınırdır bu. Her duyguyu tarifederek tanımaya, duyguların bedende bıraktığı izi sürerek, duyguları tarifeder. Yazılı bir metin gibi duyguyu aklederek üstlenmeye çalışır. Öfkenin,tramvanın, bağların biçimlendirdiği benlik onun ruhsallığında daimî bir beyazsayfadır. Benliğin sürekli çocukluk kulesinde damarlanıp kanlanan bir bilinçküresi olduğunu söylersek, Badem’in kahramanı zeki ama benliksizdir (egosuz).O bir hilkat garibesidir. Dolayısıyla onu direkt hastalığıyla, yani Aleksitimiile adlandırabiliriz. Aleksitimi’nin marazi organik sınırı, kahramanı korkuyubilmediği için cesur, sevinci bilmediği için durgun, telaşı bilmediği içinsakin kılar. Bilinci dinlendirmeye çalıştığımız, türlü meditasyon yöntemleriylebenliğimizi baştan ele almayı öğrendiğimiz şu günlerde, duyguların esiri olanmodern insanın karşısına bir hilkat garibesi olarak çıkar Aleksitimi, gerçekbir fenomen olarak. Temel duyuları fazlasıyla gelişmiş olsa da temas ettiğinesneyi birer imgeye ya da mecaza çevirecek içgüdülerden, sezgilerden ve duyumlardantümüyle yoksun, sadece tasvir bölgesinde kalır. Kahramanın tasvirde bu denlibaşarılı olmasının nedeni şiirsizliğidir. Mecazi anlamda kalpsizliğidir. Anlatıboyunca Aleksitimi’nin gözünden anlatılan habitat, duygudan, dolayısıylaruhsallıktan tümüyle arık olmasına karşın anlatının bu denli yüksek birtasvirle kuşatılması gerçekten çok çarpıcı. Hayat var ama duyumsal (sensualite)iz kayıp. Geçmiş somut biçimlerle mutlaklaşırken,bellek sıradüzenli (kronolojik) dizilen bir albümün dışına çıkamıyor.Kronos’un hükmünde araçsallaşan geçmiş, Kozmos’un helezonik ve çok anlamlıalgılarından tümüyle kopuk, bomboş bir coğrafyayı andırıyor. Roman boyunca akledenbedenden başka hiçbir şey olamayan bir insanın hikâyesindeki bütün trajik yükokura bırakılıyor. Dokunaklı biranlatının bütün hislerini üstlenirken buluyoruz kendimizi.

Heykelkıpırdayabilir sanki değil mi, her an kıpırdayabilir, heykel kıpırdamak üzere.

Geçmişinhafızasız olabileceğini gösteren çok çarpıcı bir okuma olarak ele alabilirizBadem’i. Kahramanın en başta hayatta kalması ve toplumla uyumlanabilmesi içinduygunun biçimlendirdiği ortak davranışları öğrenerek taş kalpli görünmektenkurtulması gerekiyor. Ama bu yetmiyor. İnsanı insani yapan sadece çevreyeuyumlanmak değildir çünkü, onu benzersiz bir biçimde biçimlendiren oikostur. Dünyayısoyutlaştıran en çirkinden en latife uzanan sıfatların, mecazların ve imgelerinpeşinde kişi benliğini bulur.

Elbetteher benlik geçicidir. Her benlik deneyimler eşliğinde yeni biçimler alır, kunt,değişmez, katı bir varlık değildir. Badem’in Aleksitimi’sindeki gibizihnimizdeki o boş sayfa da olasılıklar manzumesidir aynı zamanda. Ama asılburada değinmek istediğim benliğin doğal potansiyelinin gerisinde, duyumsalsınırın karanlık tarafında yaşam süren kahramanın çözüldüğü, yani dönüşmeyebaşladığı süreç olacak. Yaşadığı korkunç olayların sonunda ne yas ne yalnızlıkne suçluluk ne de keder hissedebilen kahramanız ancak bu duyguları fazlasıylayaşayan bir akranıyla sürdürdüğü zorlu temasta oikosu keşfetmeye başlar. Birucubeyi ancak öbür ucube iyileştirebilecektir. Kahramanın insanlığa geçişi, başkabir ‘normal’ insan olamayanla kurduğu ilişkide parlar.

Sınır-geçiş-dönüşümtemasını beklenmedik bir patikadan haritalayan bu roman, duyguların kalptenbeyine aldığı yolu alt üst ederek, serüveni beyinden başlatıp kalpte son bulduruyor.Dolayımlı göndermelerle romanın okura sunduğu en çarpıcı önerme şu: ahlâkındağarcığı kalptir, beyinse sadece ahlaki yasayı işleten canlı bir konak. Enönemli ikinci önerme ise, benzerlerin asla birbirini dönüştüremeyeceği. Sözkonusu benlik olduğunda birbirine yaklaşan, yaklaştıkça çatışan, çatıştıkçakanayan her benzemez, öteki için ilahi bir metindir. Nasıl ki müzedeki Antinousbir oğlanın gözünde kımıldamak üzere 1900 yıldır oradaysa, onu seyreden oğlanda Antinous için yontulmaya hazır olası bir şairdir.

-

Source : KOREAN LITERATURE NOW, https://www.kln.or.kr/lines/reviewsView.do?bbsIdx=161

Provider for

Keyword : Almond,Sohn Won-Pyung,KLN,KOREAN LITERATURE NOW

- Badem

- Author : Won-Pyung Sohn

- Co-Author :

- Translator : Tayfun Kartav

- Publisher : Peta Kitap

- Published Year : 2021

- Country : TURKIYE

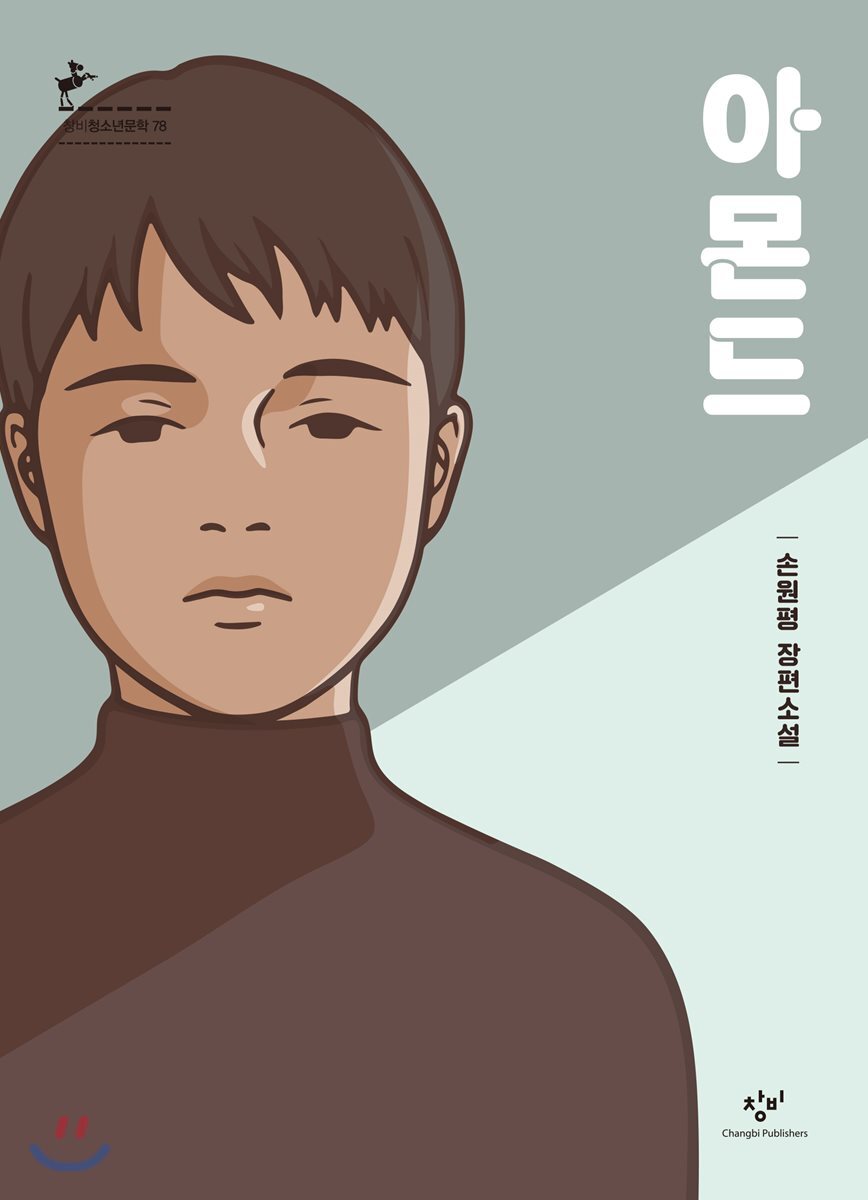

- Original Title : 아몬드

- Original Language : Korean(한국어)

- ISBN : 9786257232067

- 아몬드

- Author : Sohn Won-pyung

- Co-Author :

- Publisher : 창비

- Published Year : 0

- Country : 국가 > SOUTH KOREA

- Original Language : Korean(한국어)

- ISBN : 9788936456788

Translated Books29 See More

E-News119 See More

-

Japanese(日本語) OthersK−POP・韓流ドラマ人気の次は? 韓国文学ブーム「日本人も腑に落ちる」

-

Spanish(Español) Others‘Almendra’, el viento, una historia del no sentir de Won-pyung Sohn

-

Japanese(日本語) Others2020年本屋大賞は凪良ゆう『流浪の月』 “普通”を揺さぶる、引き離された男女の物語