도입부

문순태(1941~)는 한국의 소설가다. 1965년 현대문학에 시 <천재들>로 추천을 받고, 1974년 백제 유민의 삶을 그린 단편 <백제의 미소>가 당선되면서 등단했다. 작품 활동을 시작한 이후에는 작가 자신의 고향의 역사와 현실을 주로 소설로 형상화했다.

생애

문순태는 1941년 3월 15일 전남 담양에서 출생했다. 전남대학교 철학과에 입한 후 숭실대학교에 편입했다가 조선대학교 국어국문학과를 졸업했다. 1950년 6월 전쟁 이후 광주에서 생활했다. 시인 김현승의 추천으로 1965년 ≪현대문학≫에 시 <천재들>을 발표했다. 1965년에는 ≪전남매일신문≫에서 기자로 일했다. 1974년 <백제의 미소>가 ≪한국문학≫ 신인상에 당선되었다. 1985년 순천대학교 국어교육학과 조교수로 일했고, 1989년에는 ≪전남일보≫ 편집국장으로 일했다. 1996년 광주대학교 문예창작과 교수로 부임 후, 2006년에 정년퇴임했다. 정년퇴임 이후 고향 전남 담양군 남면 만월리 생오지에서 후진을 양성중이다. 1982년 제1회 문학세계 작가상을 수상했으며. 대표작으로는 ≪징소리≫(1978) 연작을 비롯하여 ≪타오르는 강≫(1980), ≪철쭉제≫(1981), ≪피아골≫(1982~1984), ≪녹슨 철길≫(1989) 등이 있다.

작품세계

문순태의 소설은 유년 시절의 원체험과 민족의 분단 문제 등이 현실과 융합하여 새로운 주제로 확산되어 간다. 또한 작가는 고향과 어머니를 소설 속에서 중요하게 다루었는데, 이는 자신의 작품이 고향과 어머니에서 비롯되었다고 판단했기 때문이다.1) 문순태는 역사를 바라볼 때 중립적인 자세를 취했다. 분단 이후 한국사회에 계속되었던 대립과 갈등을 다루면서도 어느 한쪽에 치우치지 않고 민족적 동질성이라는 측면에서 접근해, 전후소설의 새로운 장을 마련했다는 평가를 받고 있다.2)

‘한恨의 민중사’라는 부제가 붙은 소설 ≪타오르는 강≫은 영산강을 모태로 살아가는 노비들의 이야기다. 노비의 삶에서 벗어나기 위해 도망쳤다가 주인에게 붙잡혀 온 주인공 웅보의 이야기가 작품의 중심이다. 웅보의 할아버지 역시 노비로 살기 싫어 세 번이나 도망갔다가 잡혀와 이마에 ‘노비’라는 불도장을 찍혔다. 웅부의 할아버지는 죽으면서 이마의 불도장을 지워달라는 부탁을 한다. 또한 소설 ≪타오르는 강≫은 독특한 서사와 전설 그리고 전라도 토속어가 특징적이고, 방대한 양의 사료를 수집하여 서사화했다. 가령, 만민공동회와 황국협회 회원들 간의 난타전에 관한 묘사, 초라한 행색의 ‘의병’과 일본 헌병대의 전투 장면을 통해 작가가 사료 수집에 심혈을 기울였음을 확인할 수 있다.3)

<철쭉제>의 주인공 '나'는 6 25 때 아버지를 학살한 원수를 갚기 위해 고향에 내려간다. 그곳에서 나는 아버지를 죽인 '박판돌'과 철쭉제가 열리는 세석평전으로 가서, 아버지의 유골을 찾는다. 돌연히 사라졌던 박판돌은 자신의 어머니에 관한 이야기를 들려준다. 판돌의 어머니 넙순이 노비로 있을 때, '나'의 조부 박 참봉에게 성폭행을 당했다. 넙순이가 결혼을 한 뒤에도 그녀를 강간했던 박참봉은 자신의 잘못이 드러나자 족보에 올려 준다는 약속을 한다. 그러나 박참봉의 아들인 '나'의 아버지가 박쇠(넙순의 남편)를 지리산에서 엽총으로 살해한다. 이야기를 들은 '나'(박 검사)는 박판돌에게 내년 철쭉제에서 다시 만날 것을 약속하고 악수를 청한다.4)

고향 상실의 비극을 다룬 ≪징소리≫연작의 주인공 칠복은 어릴 때 부모를 잃고 머슴처럼 컸다. 청년이 된 칠복은 순덕과 결혼했지만 도시의 삶을 좋아하던 순덕과 칠복의 생활은 순탄하지 않았다. 칠복은 순덕이 다른 남자와 도망을 간 후, 빈손으로 딸과 함께 고향에 돌아온다. 그는 알 수 없는 이유로 징을 애지중지한다. 사람들은 마을의 주요 수입원인 낚시꾼들을 방해하는 징을 뺏으려 했으나, 매번 실패했다. 마침내 마을에서 칠복을 내쫓기로 하고, 칠복과 그의 딸을 읍에 가는 버스에 태운다. 칠복의 친구인 봉구는 칠복이 떠난 후, 봉구는 바람 소리인지 징 소리인지 모를 소리를 듣는다. 마을 사람들도 귀기(鬼氣)가 느껴지는 징 소리에 몸을 떨며 잠을 뒤척인다.5)

문순태는 소설에서 1980년 광주민주화항쟁을 직/간접적 소재로 사용하고 있는데, 1986년에 발표한 <달빛 골짜기 통곡>도 이에 해당하는 작품이다. <달빛 골짜기 통곡>은 소설 속 공간을 명시적으로 광주라고 밝히지는 않았지만 여인의 호곡소리를 5.18광주민주화운동 때 행방불명된 자들의 곡소리로 상치시키고 있다. 또한 <생오지 뜸부기>에서 주인공은 53년 만에 돌아와 오염되어 황폐해진 고향을 발견하고 다른 존재와 더불어 사는 삶에 관심을 갖게 된다.

주요 작품

≪고향으로 가는 바람≫, 창작과비평사, 1977

≪흑산도 갈매기≫, 백제, 1979

≪걸어서 하늘까지≫, 창비, 1980

≪타오르는 강≫, 창비, 1981

≪물레방아 속으로≫, 심설당, 1981

≪달궁≫, 문학세계사, 1982

≪아무도 없는 서울≫, 태창문화사, 1982

≪병신춤을 춥시다≫, 문학예술사, 1982

≪철쭉제≫, 삼성출판사, 1983

≪피울음≫, 1983

≪인간의 벽≫, 나남, 1985

≪피아골≫, 정음사, 1985

≪살아있는 소문≫, 문학사상사, 1986

≪꿈꾸는 시계≫, 동광출판사, 1990

≪제3의 국경≫, 예술문화사, 1993

≪시간의 샘물≫, 실천문학사, 1997

≪된장≫, 이룸, 2002

≪징소리≫, 일송포켓북, 2005

≪41년생 소년≫, 랜덤하우스 중앙, 2005

≪울타리≫, 이룸, 2006

≪생오지 뜸부기≫, 책 만드는 집, 2009

수상 내역

1982년 제1회 문학세계 작가상

2004년 제13회 광주문화예술상 문학상

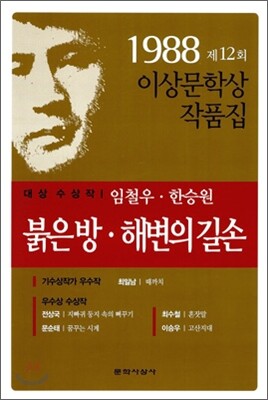

2004년 제28회 이상문학상 특별상

2006년 제23회 요산문학상 수상(수상작「울타리」)

2010년 제7회 채만식문학상

참고 문헌

1) 고봉준 외, 『문순태 소설의 시대정신』, 국학자료원, 2018

2) 김윤식, 「우리 소설의 표정 – 문순태의 ≪물레방아 속으로≫」, 문학사상사, 1981

3) 황광수, 「과거의 재생과 현재적 삶의 완성」, 『타오르는 강』, 창작과 비평, 1983

4) 권영민, 「이야기를 말하는 방식문제」, 『인간의 벽』, 문학사상, 1984.9

5) 조은숙, 「문순태 소설의 지형도 연구」, 현대문학이론연구 66, 2016

Introduction

Mun Suntae (1941~) is a South Korean Writer. He was recommended for the Hyundae Munhak for his poem “Cheonjaedeul” (천재들 Geniuses) in 1965 and made his debut in 1974 with “Baekjeui Miso” (백제의 미소 Smile of Baekje), a short story portraying the lives of Baekje refugees. Ever since he started his career as a professional writer, he has mainly written novels projecting the history and the reality of his hometown.

Life

Mun Suntae was born in Damyang, Jeollanam-do on March 15, 1941. He entered Cheonnam National University as a philosophy major and transferred to Soongsil University before he finally graduated from the Department of Korean Language and Literature, Chosun University. He has lived in Gwangju since the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950. Recommended by a poet Kim Hyunseung, he published his poem “Cheonjaedeul” in the Hyundae Munhak in 1965, when he was working for the Chunnam Maeil as a journalist. In 1974, his short story, “Baekjeui Miso” won the Korean Literature New Writer’s Award. He used to be an assistant professor at Sunchon National University in 1985, and the chief editor of the Jeonnam Ilbo in 1989. In 1996, he was appointed as a professor to teach creative writing at Gwangju University, where he made regular retirement in 2006. He has been raising younger writers since the retirement in his hometown Saengoji, a village in Manwol-ri, Nam-myeon, Damyang-gun, Jeollanam-do. He won the 1st Munhaksegye Writer Award (문학세계 작가상) in 1982. His major works include Jing Sori (징소리 The Sound of the Jing, 1978) series, Taoreuneun Gang: Hanui Minjungsa (타오르는 강: 한의 민중사 The Burning River: The Sorrowful History of People, 1980), Cheoljjukje (철쭉제 Royal Azalea Festival, 1981), Piagol (피아골 Piagol, 1982-1984) and Nokseun Cheolgil (녹슨 철길 The Dusty Railroad, 1989).

Writing

Mun Suntae’s novels merge his original experiences in childhood and the problem of north-south division with reality to expand into a new theme. In addition, hometown and mother are the elements dealt with importance, since those are what he thinks his works are based on.[1] Mun Suntae assumes a neutral attitude towards history. He is considered to have opened a new chapter of post-war novel by emphasizing ethnic homogeneity instead of taking one side when tackling problems of conflict and discord continuing since the north-south division.[2]

Taoreuneun Gang, subtitled “Hanui Minjungsa” (한의 민중사 The Sorrowful History of People), is a story of slaves living along the Yeongsan river. The story focuses on the life of the protagonist Ungbo, who tries to run away from slavery but gets caught by his owner. Ungbo’s grandfather had also run away three times for the same reason but got caught and branded ‘slave’ on his forehead. In his dying breath, Ungbo’s grandfather asks Ungbo to erase the brand on his forehead. The novel Taoreuneun Gang is based on massive amount of data, featuring unique narratives, folk tales and Jeolla-do dialect. For example, description of a fierce battle between the People’s Joint Association and the Japanese Empire Association or a battle between shabby “Uibyeong (righteous army)” and Japanese military shows that the author devotedly collected background resources.[3]

Cheoljjukje is narrated by the protagonist Prosecutor Park in the first person. Prosecutor Park returns to hometown to take revenge on the enemy who killed his father during the Korean War. He visits Seseokpyeongjeon – where Cheoljjukje (Royal Azalea Festival) takes place – and finds his father’s remains with “Park Pandol,” who killed his father. Park Pandol tells a story of his mother. Pandol’s mother Neobsun was a slave and was raped by Prosecutor Park’s grandfather, Park Chambong (officer Park). He continued to rape her even after her marriage. When all his wrongdoings were unfolded, Park Chambong promised to accept the child into his family. However, Park Chambong’s son, that is, Prosecutor Park’s father, killed Park Soe (Neobsun’s husband) with a hunting gun on Mt. Jiri. After listening to all this story, “I” (Prosecutor Park) asks Park Pandol to see each other on the next Cheoljjukje, holding out his hand.[4]

Jing Sori series deal with the tragedy of the loss of hometown. Chilbok, the protagonist, lost his parents when he was young and grew up as a family servant. As an adult, Chilbok marries Sundeok, who preferrs unban life, and their married life is not so smooth. Sundeok finally runs away with another man and Chilbok returns to hometown empty-handed with his daughter. He treasures jing (Korean traditional instrument) for an unknown reason. People try to take the jing away from him because it disturbs fishing, the village’s major source of income, but repeatedly fail. At last, people of the village force Chilbok and his daughter to ride a bus heading downtown, determined to kick them out. After they leave, Chilbok’s friend Bonggu hears a sound of which he cannot be sure if it is wind or the jing. People of the village also toss and turn, shivering at the ghastly sound of jing.[5]

Mun Suntae features the Gwangju Democratization Movement of 1980 in his works, directly or indirectly. One of such works is “Dalbit Goljjagi Tonggok” (달빛 골짜기 통곡 Wailing of the Moonlit Valley), published in 1986. Although not explicitly set in Gwangju, the novel juxtaposes a woman’s wailing with weeping of people who are lost during the Gwangju Democratization Movement. Also, in Saengoji Ddeumbugi, the protagonist returns to his hometown after 53 years to find it contaminated and devastated. He comes to be interested in living together with different beings.

Notable Works

≪고향으로 가는 바람≫, 창작과비평사, 1977 / Gohyangeuro Ganeun Baram (The Wind Heading Hometown), Changbi Publishers, 1977

≪흑산도 갈매기≫, 백제, 1979 / Heuksando Galmaegi (A Seagull of Heuksando), Baekje, 1979

≪걸어서 하늘까지≫, 창비, 1980 / Geoleoseo Haneulkkaji (Walking Up to the Sky), Changbi, 1980

≪타오르는 강≫, 창비, 1981 / Taoreuneun Gang (The Burning River), Changbi, 1980

≪물레방아 속으로≫, 심설당, 1981 / Mulrebanga Sogeuro (Into a Mill Wheel), Simseoldang, 1981

≪달궁≫, 문학세계사, 1982 / Dalgung (Dalgung), Munhaksegyesa, 1982

≪아무도 없는 서울≫, 태창문화사, 1982 / Amudo Eomneun Seoul (Seoul with Nobody), Taechangmunhwasa, 1982

≪병신춤을 춥시다≫, 문학예술사, 1982 / Byeongsinchumeul Chupsida (Let’s Dance a Cripple Dance), Munhagyesulsa, 1982

≪철쭉제≫, 삼성출판사, 1983 / Cheoljjukje (Royal Azalea Festival), Samseong, 1983

≪피울음≫, 1983 / Piureum (The Bloody Crying), 1983

≪인간의 벽≫, 나남, 1985 / Inganui Byeok (The Wall of Human), Nanam, 1985

≪피아골≫, 정음사, 1985 / Piagol (Piagol), Jeongeumsa, 1985

≪살아있는 소문≫, 문학사상사, 1986 / Sarainneun Somun (The Rumor Alive), Literature & Thought, 1986

≪꿈꾸는 시계≫, 동광출판사, 1990 / Kkumkkuneun Sigye (The Dreaming Clock), Donggwang, 1990

≪제3의 국경≫, 예술문화사, 1993 / Jesamui Gukgyeong (The Third Border), Yesulmunhwasa, 1993

≪시간의 샘물≫, 실천문학사, 1997 / Siganui Sammul (The Spring Water of Time), Silcheonmunhaksa, 1997

≪된장≫, 이룸, 2002 / Doenjang (The Soybean Paste), Irum, 2002

≪징소리≫, 일송포켓북, 2005 / Jingsori (The Sound of the Jing), Ilsong Pocket Book, 2005

≪41년생 소년≫, 랜덤하우스 중앙, 2005 / Sasibillyeonsaeng Sonyeon (The Boy Who Was Born in 1941), Randomhouse Jungang, 2005

≪울타리≫, 이룸, 2006 / Ultari (The Fence), Irum, 2006

≪생오지 뜸부기≫, 책 만드는 집, 2009 / Saengoji Ddeumbugi (A Watercock of Saengoji), Chaekmandeuneunjip, 2009

Awards

The 1st Munhaksegye Writer Award (문학세계 작가상, 1982)

The 13st Gwangju Culture & Art Literary Award (광주문화예술상 문학상, 2004)

The 28th Yi Sang Literary Award Special Prize (이상문학상 특별상, 2004)

The 23rd Yosan Literary Award (요산문학상, 2006) (Award-winning novel “Ultari (울타리 The Fence)”)

The 7th Chae Man-Sik Literary Award (채만식문학상, 2010)

References

[1] 고봉준 외, 『문순태 소설의 시대정신』, 국학자료원, 2018 / Go Bongjun et el, The Zeitgeist of Mun Suntae’s Novel, Kookhak Archives, 2018

[2] 김윤식, 「우리 소설의 표정 – 문순태의 ≪물레방아 속으로≫」, 문학사상사, 1981 / Kim Yunsik, “The Expression of Korean Novel – Mun Suntae’s Mulrebanga Sogeuro (물레방아 속으로 Into a Mill Wheel),” Literature & Thought, 1981

[3] 황광수, 「과거의 재생과 현재적 삶의 완성」, 『타오르는 강』, 창작과 비평, 1983 / Hwang Gwangsu, “Regeneration of the Past and Completion of the Life of the Present,” Taoreuneun Gang (타오르는 강 The Burning River), Changbi Publishers, 1983

[4] 권영민, 「이야기를 말하는 방식문제」, 『인간의 벽』, 문학사상, 1984.9 / Kwon Yeongmin, “The Issue of the Mode of Storytelling,” Inganui Byeok (인간의 벽 The Wall of Human), Literature & Thought, 1984.9

[5] 조은숙, 「문순태 소설의 지형도 연구」, 현대문학이론연구 66, 2016 / Jo Eunsuk, “A study on Topography in the Novel of Moon Sun-tae, Research on Contemporary Literature Theory 66, 2016