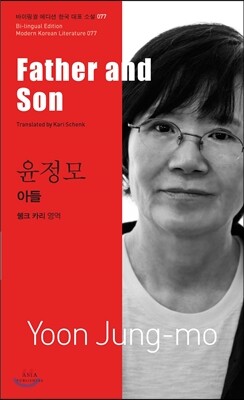

윤정모(소설가)

1. 도입부

윤정모는 1980~90년대 한국의 역사적 현실을 소재로 한 주목할 만한 장편소설을 발표하며 이름을 알린 소설가이다. 윤정모 소설에 짙게 깔린 인간에 대한 신뢰와 역사의 진보에 대한 전망은 때론 “감상주의적”이라는 평가를 받긴 하지만 그것 자체가 나름의 역사적 총체성을 구현하는 방식이라고 이해가 가능하다. 방현석은 윤정모를 지칭하며 “젊은 문학인들, 특히 민족문학의 울타리 안에서 나를 앞뒤로 한 세대에게 가장 좋아하는 선배를 꼽으라면” “아마 윤정모가 일등”일 것이라고 말한 적이 있다. 이는 작가적 열정이나 인간적 미덕에서 윤정모가 얻고 있는 신뢰를 짐작하게 한다. 방현석은 “진정성”이라는 단어를 사용하며 윤정모가 작품 내에서 보여주는 삶에 대한 열망과 그의 행동이 그리 다르지 않음을 말한다.

2. 생애

윤정모는 1946년 경북 월성에서 태어났다. 이혼한 어머니를 따라 내려간 외가에서 외삼촌들의 영향을 받으며 성장하였다. 부산 혜화여고를 거쳐 서라벌예술대학교 문예창작과에서 소설가 김동리의 지도로 소설을 공부하였다. 1968년 장편 『무뉘져 부는 바람』을 출간하면서 작품 활동을 시작하여 『그래도 들녘엔 햇살이』(1972), 『생의 여로에서』(1973), 『저 바람이 꽃잎을』(1973) 등을 잇달아 출간하였다. 대학 졸업 후 여러 출판사에서 교정을 보며 일을 하였다. 1981년 『여성중앙』 중편 현상공모에 「바람벽의 딸들」이 당선되어 정식으로 문단에 데뷔하였다.

윤정모는 1980년 5월 광주에서 여성회를 하던 홍희담(『깃발』을 쓴 소설가)에게 광주민주화운동의 수배자 두 사람을 숨겨주면 매달 생활비를 20만원씩 주겠다는 제안을 받고 생활고 때문에 이를 수락한다. 그후 그들에게 윤정모는 사회와 역사에 대한 많은 것을 배웠다고 토로한다. 윤정모는 광주민주화운동을 직간접적으로 겪으며 한국 민족사의 비극과 분단 현실, 계급 간의 갈등, 여성의 수난 등을 본격적으로 탐색하기 시작했다. 「등나무」(1983), 「밤길」(1985), 「님」(1985), 『고삐』(1988) 등 1980년대를 대표하는 작품들은 광주민주화운동에서 비롯된 분노와 저항감을 문학적으로 껴안으려는 열정의 소산이었다.

1990년대 이후 윤정모는 보다 넓은 시각으로 역사와 현실의 문제를 소설로 형상화하였다. 농촌 문제, 망명 음악인 윤이상, 한국과 아일랜드의 비극적 현실 등을 장편으로 발표하였다. 최근에는 일본 위안부 문제를 정면으로 다룬 「에미 이름은 조센삐였다」(1982)를 「봉선화」로 각색하여 연극무대에 올리기도 하였다.

3. 작품 세계

윤정모는 1980년 광주민주화 운동 이후 문학적 시야를 현실 사회에 대한 비판으로 옮기면서 민족사의 비극적 체험에 해당하는 식민지 시대의 민족 현실과 분단 상황을 비롯하여 사회적 빈부계층의 대립과 갈등 문제 등에 대해 진지한 자세로 접근해 들어가게 된다.

일제 말기의 여성 군대 위안부 이야기를 다룬 중편 「에미 이름은 조센삐였다」, 일제 시대 나환자들의 항쟁사를 다룬 장편 『섬』(이후에 「그리고 함성이 들렸다」로 개작), 성의 상품화와 외세 지배와의 관계를 그린 장편 『고삐』, 독일에서 활동한 작곡가 윤이상의 삶을 통해 예술적 성취와 민족적 불행의 엇갈림을 형상화한 장편 『나비의 꿈』 등은 모두 이같은 작가 의식을 잘 드러내고 있는 작품들이다.

이 작품들은 특히 작가 자신이 직접 경험하거나 취재하고 수집한 자료들을 바탕으로 하여 역사적 진실성을 담보하고 있으면서도 이를 생동감 넘치는 묘사와 서술을 통해 그려냄으로써 문학적 형상화에 있어서도 높은 수준을 획득하고 있는 것으로 평가받고 있다. 2000년대 이후 수메르 문명에 대한 끈질긴 탐색의 결과물인 『수메리안』(2005), 『길가메시』(2007), 『수메르』(2010) 등을 발표하였다.

4. 주요 작품

[소설]

『저 바람이 꽃잎을』, 동민문화사, 1972.

『무늬져 부는 바람』, 오륜출판사, 1973.

『그래도 들녘엔 햇살이』, 범우사, 1973.

『생의 여로에서』, 고려문화사, 1973.

『13월의 송가』, 집현각, 1975.

『광화문통 아이』, 서음출판사, 1976.

『관계』, 서음출판사, 1977.

『독사의 혼례』, 지소림, 1978.

『너의 성숙은 거짓이다』, 산하, 1980.

『밤길』, 문예출판사, 1983.

『섬』, 한마당, 1983.

『가자, 우리의 둥지로』, 문예사, 1985.

『그리고 함성이 들렸다』, 실천문학사, 1986.

『님』, 한겨례, 1987.

『빛』, 동아, 1991.

『들』, 창작과비평사, 1992.

『고삐』, 풀빛, 1993.

『고삐2』, 풀빛, 1993.

『봄비』, 풀빛, 1994.

『굴레』, 인문당, 1994.

『나비의 꿈』, 한길사, 1996.

『에미 이름은 조센삐였다』, 당대, 1997.

『그들의 오후』, 창작과비평사, 1998.

『딴 나라 여인』, 열림원, 1999.

『슬픈 아일랜드』, 1-2, 열림원, 2000.

『꾸야삼촌』, 다리미디어, 2002.

『수메리안』 1-2, 파미르, 2005.

『길가메시』, 파미르, 2007.

『수메르』 1-3, 다산책방, 2010.

[수필]

『황새울 편지』, 푸른숲, 1990.

『우리는 특급열차를 타러 간다』, 눈과마음, 2001.

[기타]

『전쟁과 소년』, 푸른나무, 2003.

『누나의 오월』, 산하, 2005.

『봉선화가 필 무렵』, 푸른나무, 2008.

『수난 사대』, 웃는돌고래, 2015.

5. 수상 내역

1988년 신동엽 창작기금

1993년 단재 문학상

1996년 서라벌 문학상

6. 같이 보기

유기성, 「『고삐』 작가 윤정모의 운동적 삶」, 『월간 말』, 1989년 6월호.

임헌영, 「우리 시대의 거울로서의 윤정모」, 『우리 시대의 소설읽기』, 글, 1992.

김성호, 「사실적 문학과 시적 문학 : 윤정모 장편 『들』을 읽으며」, 『창작과비평』, 1992년 가을호.

신윤덕, 「윤정모의 절대적 고독과 희망」, 『월간 말』, 1993년 1월호.

방현석, 「시리도록 선명한 문학적 긍지-이 계절의 작가 윤정모」, 『실천문학』, 1996년 겨울호.

고미숙, 「‘덴동어미’와 ‘이갈리아의 딸’을 넘어서-여경자의 『사랑의 상처』와 윤정모의 『그들의 오후』」, 『비평기계』, 소명출판, 2000.

고명철, 「다시 타오를 민족문제에 대한 역사적 각성-윤정모, 『슬픈 아일랜드』」, 『실천문학』, 2000년 겨울호.

최은경, 「윤정모의 『고삐』를 통해서 본 여성의 경험과 자아의 구성」, 서울대 학위논문, 2004.

송명희, 「윤정모의 『고삐』에 나타난 제3세계 민족주의의 페미니즘」, 『비평문학』, 청원, 1994.

「『고삐』 작가 윤정모의 영국생활」, 『여성동아』, 1999.11.

Yun Jeong-Mo

1. Introduction

Yun Jeong-Mo (born 1946) is a South Korean writer. She was born in Wolseong, North Gyeongsang Province, and graduated Hyehwa Girls’ High School in Busan. She studied creative writing and literature at Seorabeol Art University, during which she wrote her first novel Munuijyeo buneun baram (무늬져 부는 바람 Winds Filled with Patterns). The novel was published in 1968, quickly followed by a number of other works: Geuraedo deulyeogen hetsari (그래도 들녘엔 햇살이 Still There Is Sunshine on the Fields) in 1972, Saengui yeoroeseo (생의 여로에서 On the Road of Life’s Journey) in 1973, and Jeo barami kkotnipeul (저 바람이 꽃잎을 Flower Petals in That Wind) in 1973. Her 1981 novella Barambyeokui ttaldeul (바람벽의 딸들 Daughters of the Wall) won the Yeoseong Joongang Contest. In 1988, she received the Sin Dong-yup Grant for Creative Writing and the Danjae Literature Prize. Her recent works include the short story collections Sumerian (수메리안 Sumerian) and Gilgamesh (길가메시 Gilgamesh), which were published in 2005 and 2007, respectively. She also has a fan page.

2. Life

Yun was born in Wolseong, North Gyeongsang Province, in 1946. She grew up under the influence of her uncles at her maternal grandparents’ home, to which she had followed her mother when her parents divorced. She attended Hyehwa Girls’ High School in Busan and studied creative writing under novelist Kim Dong-ni at Seorabeol Art University. She began writing in earnest, and in 1968 her first novel Munuijyeo buneun baram (무늬져 부는 바람 Winds Filled with Patterns) was published. After graduating university, she worked as a proofreader for several publishers. She made her official literary debut when Barambyeokui ttaldeul (바람벽의 딸들 Daughters of the Wall) won the Yeoseong Joongang Contest in the Novella category.

In May 1980, Hong Hee-dam, author of Gitbal (깃발 Flag) and a member of a women’s organization in Gwangju, asked Yun to hide two Gwangju Uprising activists wanted by the government and offered a monthly payment of KRW 200,000 in return. Struggling to make ends meet, she accepted. She ended up learning a lot about history and society from the two activists, as she would later confess. Experiencing the Gwangju Uprising both directly and indirectly, Yun began to explore the sad history of the Korean people, the reality of the peninsula’s division, class struggles, and the plight of women. The rage and defiance she felt towards the Gwangju Uprising were channeled into creative expression, resulting in novels that are now representative of South Korea in the 1980s. Examples include Deungnamu (등나무 Wisteria, 1983), Bamgil (밤길 Night Road, 1985), Nim (님 Thee, 1985), and Goppi (고삐 Reins, 1988).

Since the 1990s, Yun has written novels that reflect a broader view of history and reality. These novels deal with topics ranging from the concerns of farming communities to the life of Yun I-sang (a South Korean-born composer who defected to Germany) to the tragic realities of Korea and Ireland. Recently, she adapted her 1982 novel Emi ireumeun josenppiyeotda (에미 이름은 조센삐였다 Your Ma's Name Was Chosun Whore) into a play entitled Bongseonhwa (봉선화 Touch-me-not). These two works raise the issue of Korean “comfort women” forced into sexual slavery for Japanese soldiers during World War II.

3. Writing

Since the 1980 Gwangju Uprising, Yun has shifted her literary focus to social criticism. In particular, she has probed in depth the tragic national experience of colonization, the division of Korea, and conflicts between the rich and poor, among others.

This artistic vision is evident in many of her works: the novella Emi ireumeun josenppiyeotda (에미 이름은 조센삐였다 Your Ma's Name Was Chosun Whore) tells the story of women sexually enslaved by Japanese troops during the late colonial period; Seom (섬 Island), later revised to Geurigo hamseongi deulyeotda (그리고 함성이 들렸다 And Then We Heard the Roar), chronicles the struggles of lepers during Japanese occupation; Goppi (고삐 Reins) investigates the relationship between foreign rule and the commercialization of sex; and Nabiui kkum (나비의 꿈 A Butterfly’s Dream) illustrates the unfortunate interplay between a nation’s fate and an artist’s achievements by following the life of Korean-born German composer Yun I-sang.

Given that these works were written based on Yun’s firsthand experience and research, they are grounded in historical accuracy. They have also been recognized for literary merit due to their vividness of portrayal and expression. Since the 2000s, Yun has closely studied the Sumer civilization, based on which she wrote Sumerian (수메리안, 2005), Gilgamesh (길가메시, 2007), and Sumer (수메르, 2010).

4. Works

[Novels]

『저 바람이 꽃잎을』, 동민문화사, 1972.

Flower Petals in That Wind. Dongminmunhwasa, 1972.

『무늬져 부는 바람』, 오륜출판사, 1973.

Winds Filled with Patterns. Oryun, 1973.

『그래도 들녘엔 햇살이』, 범우사, 1973.

Still There Is Sunshine on the Fields. Bumwoosa, 1973.

『생의 여로에서』, 고려문화사, 1973.

On the Road of Life’s Journey. Goyreomunhwasa, 1973.

『13월의 송가』, 집현각, 1975.

Ode of the Thirteenth Month. Jiphyeongak, 1975.

『광화문통 아이』, 서음출판사, 1976.

The Child on Gwanghwamun Street. Seoeumchulpansa, 1976.

『관계』, 서음출판사, 1977.

Relationship. Seoeumchulpansa, 1977.

『독사의 혼례』, 지소림, 1978.

Viper's Wedding. Jisorim, 1978.

『너의 성숙은 거짓이다』, 산하, 1980.

Your Maturity Is False. Sanha, 1980.

『밤길』, 문예출판사, 1983.

Night Road. Moonye Books, 1983.

『섬』, 한마당, 1983.

Island. Hanmadang, 1983.

『가자, 우리의 둥지로』, 문예사, 1985.

Let's Go, to Our Nest. Moonyesa, 1985.

『그리고 함성이 들렸다』, 실천문학사, 1986.

And Then We Heard the Roar. Silcheon Munhak, 1986.

『님』, 한겨례, 1987.

Thee. Hanibook, 1987.

『빛』, 동아, 1991.

Light. Donga, 1991.

『들』, 창작과비평사, 1992.

Field. Changbi, 1992.

『고삐』, 풀빛, 1993.

Reigns. Pulbit, 1993.

『고삐2』, 풀빛, 1993

Reigns 2. Pulbit, 1993.

『봄비』, 풀빛, 1994.

Spring Rain. Pulbit, 1994.

『굴레』, 인문당, 1994.

Bridle. Inmundang, 1994.

『나비의 꿈』, 한길사, 1996.

A Butterfly’s Dream. Hangilsa, 1996.

『에미 이름은 조센삐였다』, 당대, 1997.

Your Ma's Name Was Chosun Whore. Dangdae, 1997.

『그들의 오후』, 창작과비평사, 1998.

Their Afternoon. Changbi, 1998.

『딴 나라 여인』, 열림원, 1999.

Foreign Woman. Yolimwon, 1999.

『슬픈 아일랜드』, 1-2, 열림원, 2000.

Sad Island Vol. 1-2. Yolimwon, 2000.

『꾸야삼촌』, 다리미디어, 2002.

Uncle Kkuya. Dari Media, 2002.

『수메리안』 1-2, 파미르, 2005.

Sumerian Vol. 1-2. Pamir, 2005.

『길가메시』, 파미르, 2007.

Gilgamesh. Pamir, 2007.

『수메르』 1-3, 다산책방, 2010.

Sumer Vol. 1-2. Dasanchekbang, 2010.

[Essay Collections]

『황새울 편지』, 푸른숲, 1990.

Letters from Hwangseul. Prunsoop, 1990.

『우리는 특급열차를 타러 간다』, 눈과마음, 2001.

We're Off to Take the Express Train, Nungwamaeum, 2001.

[Other]

『전쟁과 소년』, 푸른나무, 2003.

The War and the Boy. Purunnamu, 2003.

『누나의 오월』, 산하, 2005.

Nuna' May. Sanha, 2005.

『봉선화가 필 무렵』, 푸른나무, 2008.

When Rose Balsams Bloom. Purunnamu, 2008.

『수난 사대』, 웃는돌고래, 2015.

Tragedy over Four Generations. Smiling Dolphin, 2015.

5. Awards

1988: Sin Dong-yup Grant for Creative Writing

1993: Danjae Literature Prize

1996: Seorabol Literature Prize

6. Further Reading

유기성, 「『고삐』 작가 윤정모의 운동적 삶」, 『월간 말』, 1989년 6월호.

Yoo, Gi Seong. "Reigns Author Yun Jeong-Mo's Life of Movement." Monthly Magazine Mal, 1989 June Issue.

임헌영, 「우리 시대의 거울로서의 윤정모」, 『우리 시대의 소설읽기』, 글, 1992.

Im, Heon Yeong. "Yun Jeong-Mo as the Mirror of Our Age." In Reading Novels in this Age. Geul, 1992.

김성호, 「사실적 문학과 시적 문학 : 윤정모 장편 『들』을 읽으며」, 『창작과비평』, 1992년 가을호.

Kim, Seong Ho. "Realistic Literature and Poetic Literature: On Reading Yun Jeong-Mo's Novel Field." Changbi, 1992 Fall Issue.

신윤덕, 「윤정모의 절대적 고독과 희망」, 『월간 말』, 1993년 1월호.

Sin, Yun Deok. "Yun Jeong-Mo's Absolute Solitude and Hope." Monthly Magazine Mal, 1993 January Issue.

방현석, 「시리도록 선명한 문학적 긍지-이 계절의 작가 윤정모」, 『실천문학』, 1996년 겨울호.

Bang, Hyeon Seok. "Literary Pride That Is Dazzlingly Clear: Writer of the Season, Yun Jeong-Mo." Silcheon Munhak, 1996 Winter Issue.

고미숙, 「‘덴동어미’와 ‘이갈리아의 딸’을 넘어서-여경자의 『사랑의 상처』와 윤정모의 『그들의 오후』」, 『비평기계』, 소명출판, 2000.

Go, Mi Suk. "Beyond Dendongeomi (Mother of the Burnt Child) and Egalia's Daughters: Yeo Gyeong Ja's Scars of Love and Yun Jeong-Mo's Their Afternoon." In Criticism Machine. Somyung Books, 2000.

고명철, 「다시 타오를 민족문제에 대한 역사적 각성-윤정모, 『슬픈 아일랜드』」, 『실천문학』, 2000년 겨울호.

Go, Myeong Cheol. "Historical Eye-Opener on National Issues That Will Flare up Again: Yun Jeong-Mo's Sad Island."

최은경, 「윤정모의 『고삐』를 통해서 본 여성의 경험과 자아의 구성」, 서울대 학위논문, 2004.

Choi, Eun Gyeong. "Women's Experience and Development of Self as Seen through Yun Jeong-Mo's Reigns." Master's thesis, Seoul National University, 2004.

송명희, 「윤정모의 『고삐』에 나타난 제3세계 민족주의의 페미니즘」, 『비평문학』, 청원, 1994.

Song, Myeong Hui. "Third-World Nationalistic Feminism in Yun Jeong-Mo's Reigns." Literary Criticism, 1994.

『고삐』 작가 윤정모의 영국생활」, 『여성동아』, 1999.11.

"Reigns Author Yun Jeong-Mo's Life in the UK." W Dong-A, November 1999.